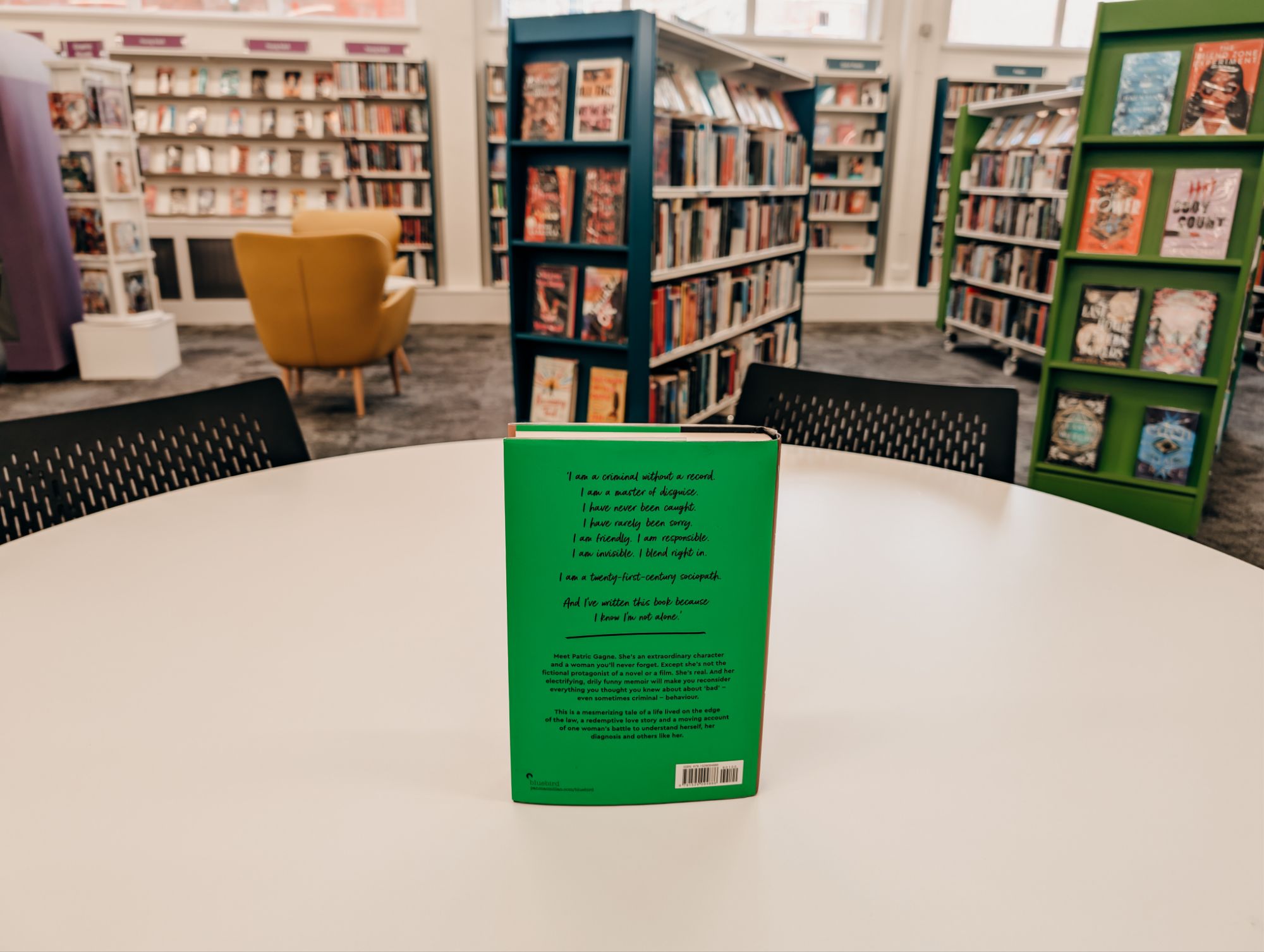

Think all sociopaths are movie villains? Think again. We gave Patric Gagne’s “Sociopath: A Memoir” 5 stars ★ ★ ★ ★ ★. Here’s why this dark, funny, and honest look at ASPD is a total page-turner.

Imagine standing in a room full of people laughing, crying, and connecting, and feeling absolutely nothing. No warmth, no shared joy, no empathy. Just a hollow silence where your emotions should be, and a rising, dark pressure demanding you do something (anything) to break the monotony. For most of us, sociopathy is the stuff of nightmares and true crime documentaries. It is the label we slap on serial killers, corporate sharks, and the cold-hearted villains of cinema. We see “them” as monsters, fundamentally broken and irredeemable. But what if the monster is just a woman trying to figure out why she doesn’t love her mother? What if the “villain” is actually a Ph.D. student desperately searching for a way to live without destroying everything in her path? In Patric Gagne’s Sociopath: A Memoir, we are handed a rare and unsettling key to the locked room of the sociopathic mind. Gagne, a diagnosed sociopath and a former therapist, attempts the impossible: she asks us to empathize with the empathy-impaired.

This review is for everyone. It is for the curious minds fascinated by psychology. It is for those who suspect they might be on the spectrum of Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). And perhaps most importantly, it is for those who have suffered at the hands of a sociopath, because understanding the mechanism of the harm is the first step toward reclaiming your power.

Gagne’s writing is electric, witty, and disarmingly honest. She describes her childhood not as a tragedy of abuse (the common trope for developing personality disorders) but as a confusing existence of emotional silence. She grew up in a loving home, yet she felt like a frantic alien trying to decode human behavior. She introduces us to “The Pressure.” This is her term for the rising tension she feels when the boredom of her apathy becomes too much to bear. For Gagne, sociopathy isn’t about enjoying cruelty; it’s about a desperate need to feel something. When the void becomes deafening, she acts out (stealing cars, breaking into houses, engaging in high-risk behaviors).

“I didn’t want to hurt anyone. I just wanted to feel the way everyone else seemed to feel. And when I couldn’t, I wanted to break things.”

The book argues that the majority of sociopaths are not violent criminals. They are your neighbors, your colleagues, perhaps even your family members, silently struggling with a brain that doesn’t process social rewards the way yours does. The memoir tracks her journey from a confused child “practicing” emotions in the mirror to a young woman navigating love and career while harboring a dark secret. It’s a compelling coming-of-age story, if the coming-of-age involved breaking and entering.😉

Where Sociopath transcends the typical memoir genre is in Gagne’s academic rigor. Realizing that the world offered no help for people like her other than prison or ostracization, she pursued a Ph.D. in psychology to understand herself. Gagne relies heavily on the work of Dr. Ben Karpman, a pivotal figure in the study of psychopathy. Karpman distinguished between:

- Secondary Psychopaths (or Sociopaths): Individuals who may have the capacity for empathy but have walled it off due to environmental factors, trauma, or other neurotic conflicts.

- Primary Psychopaths: Individuals with a constitutional deficit in affect. They are born this way, lacking the hardware for conscience or fear.

Patric Gagne identifies more with the sociopathic label – someone who is capable of learning, adapting, and perhaps even feeling in her own way, provided she understands the rules. She argues that the DSM-5’s umbrella term of “Antisocial Personality Disorder” is too broad and criminal-focused, failing to capture the internal experience of people like her who aren’t in prison but are still suffering.

The review of Patric Gagne’s “Sociopath: A Memoir” wouldn’t be complete without mentioning Dr. David Lykken and Linda Mealey, whose theories Gagne explores to explain her physiology. Lykken’s “Low Fear Hypothesis” suggests that sociopaths have a significantly higher threshold for fear. They don’t learn from punishment because the anxiety that stops a neurotypical person from doing something wrong simply doesn’t exist for them. Gagne illustrates this vividly: she recounts situations of extreme danger where her pulse didn’t even quicken.

Linda Mealey’s evolutionary psychology perspective is also touched upon – the idea that sociopathy might be a frequency-dependent evolutionary strategy. In a world of cooperators, there is an evolutionary niche for a small number of “cheaters” or “manipulators.” Gagne wrestles with this: Is she a biological mistake, or a necessary variant of the human species? Moreover,

Dr. Ben Karpman – one of the first physicians to receive credit for distinguishing between primary psychopathy and secondary psychopathy – argued that the antisocial behavior demonstrated by sociopaths is often the result of stress. Karpman theorized that, though they may share the same symptoms as primary psychopaths, secondary psychopaths are not hardwired to pursue an antisocial lifestyle and may be responsive to treatment.

There is a mention of Dr. Lykken sharing Karpman’s views on sociopathy.

Like Karpman, Lykken’s findings indicated that addressing anxiety could reduce the destructive traits of secondary sociopaths. He stressed the importance of socialization (the process through which a person’s core values and belief systems are programmed to align with the rest of society) in early childhood development.

If you or someone you know struggles with impulse control or low empathy, the Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) is a game-changer. Unlike traditional talk therapy, which focuses on “how does that make you feel” (useless for a sociopath who doesn’t feel much), REBT is logic-based. It was developed by Albert Ellis and focuses on resolving emotional and behavioral problems to lead a happier life. Patric breaks down how she uses the ABC Model to manage her “Pressure”:

- A (Activating Event): Something happens. (e.g., Someone is walking too slowly in front of her, or she feels a sudden wave of boredom).

- B (Beliefs): The irrational thought process. (e.g., “This person is in my way, they are worthless, I should shove them into traffic to make something happen.”)

- C (Consequences): The emotional or behavioral outcome. (e.g., Physical aggression or rage).

She realized she couldn’t change A (the world is annoying) and she often couldn’t control the initial flash of B (the sociopathic impulse). However, REBT taught her to Dispute (D) the beliefs. It goes something like this: “Okay, I want to shove this person. Why? Because I’m bored. Will shoving them actually fix my boredom long-term? No, it will get me arrested, which is inconvenient. What is a more logical action?” This cognitive restructuring allowed her to move from destructive impulses to “maintenance.” She doesn’t claim to be “cured”; she claims to be managed. She treats her sociopathy like diabetes; it requires daily monitoring and insulin (in her case, logic and coping strategies) to keep from becoming toxic.

If you are reading this and you have been the victim of a sociopath, your stomach might be turning. It is natural to feel resistance to humanizing people who have caused you pain. To the survivors: This book is not an excuse for the abuse you suffered. Patric Gagne is meticulous in not asking for forgiveness for sociopaths who hurt people. Instead, she offers an explanation. Understanding the mechanism of a bomb doesn’t make the explosion less deadly, but it ensures you know how to dismantle it next time.

Patric Gagne’s “Sociopath: A Memoir” provides a crucial insight for survivors. It wasn’t personal. The cruelty, the manipulation, the coldness. It wasn’t because you weren’t enough. It wasn’t because you deserved it. It was because the person across from you was operating on a different operating system, one driven by a need to stimulate a numb brain, or a total blindness to your emotional reality.

The author’s relationship with her husband, David, provides a fascinating case study for partners of people with ASPD. It shows that a relationship can work, but only with radical, brutal honesty and a partner who has strong boundaries. If you have suffered, reading this might validate your experience by showing you exactly what was happening behind the “mask of sanity.”

Why You Should Read It

For the General Reader: It’s a thriller of a life. Gagne is a charming narrator, darkly funny, self-deprecating, and incredibly sharp. It challenges your moral compass in the best way.

For the Mental Health Professional: This is a primary source document. It challenges the grim prognosis usually given to ASPD patients. The author argues that if we stop treating sociopaths like unfixable monsters and start giving them logical tools to manage their arousal levels, we can integrate them into society safely.

For the “Dark Triad” Individual: If you feel the “Pressure,” if you feel the apathy, this book is a mirror. It offers a roadmap away from prison and toward a life that, while not “normal”, can be fulfilling and love-filled.

Patric Gagne’s Sociopath: A Memoir is a brave, complicated book. It asks us to sit in the gray area between good and evil. Patric is not a saint, nor does she pretend to be. She proves that sociopathy is a spectrum. On one end, you have the violent offenders. But on the other hand, you have people like Patric, people who are desperate to connect, desperate to be “good,” but need a different manual to get there.